The Economist’s online edition has an interactive map with the actual numbers, as well as an option to look at population rather than GDP. Talk about a perspective changer!

How to keep those resolutions

It’s mid-January. Have you made any progress toward your New Year’s resolutions yet? If you are like the majority of people, the answer is, probably not. There is hope though. You can make accomplishing your resolutions easier by doing two things:

1. Write them down. You are more likely to achieve goals if you set objectives and put them on paper. Be specific about the stepping stones that will get you to the end result.

2. Invite peer pressure. Share your resolutions with others — family, friends, or a trusted colleague. Not wanting to disappoint someone can be good motivation.

| Today’s Management Tip was adapted from “How to Keep Those New Year’s Resolutions” by Steve Martin. |

One small step…

The latest from Bill Conerly:

Source: Bill Conerly Consulting (http://businomics.typepad.com)

2010 Business Year in Review

Care to take a guess at the top events affecting businesses in 2010? The struggling economy was voted the top business story of the year by U.S. newspaper editors surveyed by The Associated Press. The rest, as they say, is history.

1. Economy struggles: Climbing out of the deepest recession since the 1930s, the economy grows at a healthy rate in the January-March quarter. Still, the gain comes mainly from companies refilling stockpiles they had let shrink during the recession. The economy can’t sustain the pace. The lingering effects of the recession slow growth. The benefits of an $814 billion government stimulus program fade. Consumers cut spending in favor of building savings and slashing debt. Businesses hesitate to hire. Cities and states lay off workers. Growth slows through spring and summer. Unemployment stays chronically high. In May, the number of people unemployed for at least six months hits 6.8 million — a record 46 percent of all the unemployed. Pointing to the deficits, Congress resists backing more spending to stimulate the economy. The Federal Reserve seeks to fill the void by announcing it will buy $600 billion in Treasury bonds to try to further lower interest rates, lift stocks and coax consumers to spend. As the year closes, the economy makes broad gains. Factories produce more. Consumers — the backbone of the economy — return to the malls. Congress passes $858 billion in tax cuts and aid to the long-term unemployed. Yet more than 15 million Americans are still unemployed. Economists say a full economic recovery remains years away.

2. Gulf oil spill: An explosion at a rig used by BP kills 11 workers and sends crude oil gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. The spill devastates the fishing and tourism industries along the Gulf Coast and causes environmental damage that may last for decades. BP sets up a $20 billion fund to compensate fishermen, restaurateurs and others whose livelihoods were damaged. The oil giant still faces civil charges and a criminal investigation by the Justice Department and lawsuits from hundreds of individuals and businesses. BP’s stock market value shrinks by more than $100 billion after the April 20 disaster before bouncing about halfway back.

3. China’s rise: China passes Japan as the world’s second-biggest economy. The World Bank says it could surpass the United States by 2020. China’s gross domestic product is spread out over 1.3 billion people — amounting to about $3,600 per person. That compares with GDP in the U.S. of about $42,000 per person. In Japan, it’s about $38,000 per person. China’s thirst for raw materials and other products helps the rest of the world recover from the recession. Still, the U.S. and Europe complain that China gives its exporters an unfair competitive edge by keeping its currency artificially low.

4. Real estate crisis: Housing remains depressed despite super-low mortgage rates. The average rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage dips to 4.17 percent in November, the lowest in decades. But home sales and prices sink further. Nearly one in four homeowners owe more on their mortgages than their homes are worth, making it all but impossible for them to sell their home and buy another. An estimated 1 million households lose their homes to foreclosure, even though the pace slows after evidence that lenders mishandled foreclosure documents. Some did so by hiring “robo-signers” to sign paperwork without checking their accuracy.

5. Toyota’s recall: Toyota’s reputation for making high-quality cars is tarnished after the Japanese automaker recalls 10 million vehicles for sudden acceleration and other problems. Toyota faces hundreds of lawsuits alleging that some models can speed up suddenly, causing crashes, injuries and deaths. Toyota blames driver error, faulty floor mats and sticky accelerator pedals for the unintended acceleration. The uproar damages its business. Toyota’s U.S. sales rise just 0.2 percent through November in a year when the industry’s overall sales climb more than 11 percent.

6. GM’s comeback: General Motors stock begins trading again. It signals the rebirth of a corporate icon that fell into bankruptcy and required a $50 billion bailout from taxpayers. GM uses some proceeds from its November initial public offering to repay a portion of its bailout. (Washington still holds about a third of GM’s stock.) GM’s recovery helps rejuvenate the industry. Sales of cars and light trucks rise 11 percent through November compared with the same period in 2009. Shoppers who had put off replacing their old cars return to showrooms.

7. Financial overhaul: Congress passes the biggest rewrite of financial rules since the 1930s. The law targets the risky banking practices and lax oversight that led to the 2008 financial crisis. The law creates an agency to protect consumers from predatory loans and other abuses, empowers regulators to shut down big firms that threaten the entire system and shines more light into markets that have eluded oversight. Republican critics say the law goes too far, imposing burdensome rules that will restrict lending to consumers and small businesses.

8. European bailouts: Greece and Ireland require emergency bailouts, raising fears that debt problems will spread and destabilize global markets. European governments and the International Monetary Fund agree to a $145 billion rescue of Greece in May and a $90 billion bailout of Ireland in November. The bailouts require both countries to slash spending, triggering protests by workers. Investors fear that debt troubles will spread to Spain, Portugal and other countries, weaken the European Union and threaten the future of the euro as its common currency.

9. Facebook growth: Facebook tops the 500 million user mark. It expands its dominance of social media and further transforms how the world communicates. If it were a country, Facebook would be the world’s third-largest. Facebook tightens its privacy settings after criticism that personal information is being disseminated without users’ knowledge or permission. Founder Mark Zuckerberg is named Time magazine’s “Person of the Year” and is the subject of a high-profile movie about Facebook’s creation.

10. iPad mania: Apple Inc. unveils the iPad, bringing “tablet” computing into the mainstream and eroding laptop sales. Apple is expected to sell more than 13 million iPads this year. The iPads sell about twice as fast as iPhones did after their 2007 introduction. The price of Apple stock rockets more than 50 percent in 2010. Competitors scramble to try to catch up. They include the Dell Streak, BlackBerry PlayBook, the Samsung Galaxy Tag and HP Slate.

Commercial real estate indicator is positive

Note: This index is a leading indicator for new Commercial Real Estate (CRE) investment.

Note: This index is a leading indicator for new Commercial Real Estate (CRE) investment.

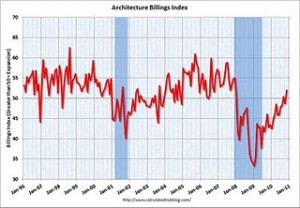

From the American Institute of Architects: Firm Billings Rebound in November

At 52.0, the AIA’s Architecture Billings Index (ABI) recorded a three point gain from the previous month, and reached its strongest level since December 2007. With ABI scores above the 50 level in two of the past three months, the prospects of a sustainable recovery in design activity are enhanced.

This graph shows the Architecture Billings Index since 1996. The index showed expansion in November (above 50) and this is the highest level since December 2007.

Note: Nonresidential construction includes commercial and industrial facilities like hotels and office buildings, as well as schools, hospitals and other institutions.

According to the AIA, there is an “approximate nine to twelve month lag time between architecture billings and construction spending” on non-residential construction. So this indicator suggests the drag from CRE investment will end next summer. This fits with other recent stories about a pickup in design activity.

Leading economic index encouraging

The Conference Board reported this week that the Leading Economic Index (LEI) for the U.S. increased in November for the fifth straight month, and for the 19th month out of the last 20 months going back to April 2009 as the recession was coming to an end and the LEI turned up (see chart by Mark Perry below).

Setting the stage for growth in 2011

The latest from Robert Barr in this week’s SAF Trend Tracker:

The nature of this recession – caused by a financial panic – means that the recovery is not playing by the customary script this time. Housing, for example, usually leads the economy out of a recession, as low interest rates spur new residential construction and home sales. But the number of troubled properties on the market remains high, even though much of the excess supply is concentrated in just a few markets. In terms of being a source of strong economic growth, housing will likely sit on the sidelines for a few more years.

The good news is that the economy is growing, albeit at a slower pace than we’d hope – and too slow a rate to bring down the unemployment rate, for now. In fact, the unemployment rate climbed in November to 9.8%, up from 9.6% in each of the three previous months. But the labor markets are always a lagging indicator of economic recovery.

Other important figures reflecting conditions more “upstream” in generating economic growth tell a different and much more positive story. For instance, corporate profits are up 28% over year-ago levels (fueling the stock market improvement). And business investment in software and equipment is booming, up 19% in the past year. That’s the strongest four quarters of growth in that segment in 26 years – even surpassing the build-up to Y2K. These developments do follow the usual story for economic recovery, as business owners, prodded by lower interest rates, add to business investment. As entrepreneurial activity and investment grow, corporate America lays the groundwork for stronger economic growth in the coming quarters.

Mix the strong activity here with the relatively strong kick-off to the holiday shopping season, and you get a strong sense that the recovery is in fact taking root – and that fears of a “double-dip” recession are overblown. And not only are the early reports from the nation’s large retailers positive, they also indicate that consumers are spending money on themselves, too – in contrast to the last few holiday seasons, when spending was more constrained.

Finally, the tax compromise that was coming together in early December could, if enacted according to the announced framework, provide some important fuel to stronger economic growth. The extension for two years of the current set of income tax rates – rather than the increase currently slated to go into effect on New Year’s Day – not only helps the entrepreneurial segment, but it ends some uncertainty, at least for now, about tax rates. The one-year cut in the Social Security payroll tax also generates a bit more cash for households, but, more importantly for economic growth, the investment expense provisions and the lower capital gains tax, currently at 15 percent, should prove to be an important business incentive.

Robert Barr is an economist based in Virginia.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (Dec 3, 2010); Bureau of Economic Analysis (Nov 23, 2010); Moody’s Analytics.

Successful outcome of climate negotiations

This is the latest blog post from Dr. Rob Stavins, Director of Harvards’s Environmental Economics program regarding the outcome of the climate negotiation in Cancun.

Successful Outcome of Climate Negotiations in Cancun

December 13th, 2010

By Robert Stavins

The international climate negotiations in Cancun, Mexico, have concluded, and despite the gloom-and-doom predictions that dominated the weeks and months leading up to Cancun, the Sixteenth Conference of the Parties (COP-16) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) must be judged a success. It represents a set of modest steps forward. Nothing more should be expected from this process.

As I said in my November 19th essay – Defining Success for Climate Negotiations in Cancun – the key challenge was to continue the process of constructing a sound foundation for meaningful, long-term global action (not necessarily some notion of immediate, highly-visible triumph). This was accomplished in Cancun.

The Cancun Agreements – as the two key documents (“Outcome of the AWG-LCA” and “Outcome of the AWG-KP”) are called – do just what was needed, namely build on the structure of the Copenhagen Accord with a balanced package that takes meaningful steps toward implementing the key elements of the Accord. The delegates in Cancun succeeded in writing and adopting an agreement that commits all major economies to greenhouse gas (GHG) cuts, launches a fund to help the most vulnerable countries, and avoids some political landmines that could have blown up the talks, namely decisions on the (highly uncertain) future of the Kyoto Protocol.

I begin by assessing the key elements of the Cancun Agreements. Then I examine whether the incremental steps forward represented by the Agreements should really be characterized as a success. And finally I ask why the negotiations in Cancun led to the outcome they did.

Assessing the Key Elements of the Cancun Agreements

First, the Cancun Agreements provide emission mitigation targets and actions (submitted under the Copenhagen Accord) for approximately 80 countries – including, importantly, all of the major economies. In this way, the Agreements require the world’s largest emitters – including China, the United States, the European Union, India, and Brazil – to commit to various targets and actions to reduce emissions by 2020. The distinction between Annex I and non-Annex I countries is blurred even more in the Cancun Agreements than it was in the Copenhagen Accord – another step in the right direction!

Also, for the first time, countries agreed – under an official UN agreement – to keep temperature increases below a global average of 2 degrees Celsius. It brings these aspirations, as well as the emission pledges of individual countries, into the formal UN process for the first time, essentially by adopting the Copenhagen Accord one year after it was “noted” at COP-15. (There’s also an abundance of politically-correct and in some cases downright silly window dressing in the Cancun Agreements, including repetitive references to various interpretations of the UNFCCC’s principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” as well as some discussion of examining a 1.5 C target.)

However, despite even the 2 degree (450 ppm concentration) aspirational target, the Agreements are no more stringent that the collection of submissions made under last year’s Copenhagen Accord. But, as Michael Levi (Council on Foreign Relations) has pointed out, the Cancun Agreement “should be applauded not because it solves everything, but because it chooses not to.” As my colleagues and I have repeatedly emphasized in our work within the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, many of the most important initiatives for addressing climate change will occur outside of the United Nations process (despite the centrality of that process).

Second, the Agreements elaborate on the mechanisms for monitoring and verification that were laid out in last year’s Accord. Importantly, these now include “international consultation and analysis” of developing country mitigation actions. Countries will report their GHG inventories to an independent panel of experts, which will monitor and verify reports of emissions cuts and actions.

Third, the Agreements establish a so-called Green Climate Fund to deliver financing for mitigation and adaptation, based on the fund proposed in the Copenhagen Accord, with a target of $100 billion annually by 2020. Importantly, the Agreements name the World Bank as the interim trustee of the Fund, despite objections from many developing countries, and create an oversight board, half of which consists of donor nation representatives.

Whether the resources ever grow to the size laid out in Copenhagen and Cancun will depend upon the individual actions of the wealthy nations of the world. However, it’s interesting that the section in the Cancun Agreements on adaptation comes before the section on mitigation. Things have come a long way since the days when economists were alone in calling for attention to adaptation (along with mitigation). I recall when economists were therefore accused of throwing in the towel, and not caring about the environment!

Fourth, the Agreements advance initiatives on tropical forest protection (or, in UN parlance, Reduced Deforestation and Forest Degradation, or REDD+), by taking the next steps toward establishing a program in which the wealthy countries can help prevent deforestation in poor countries, possibly working through market mechanisms (despite exhortations from Bolivia and other leftist and left-leaning countries to keep the reach of “global capitalism” out of the policy mix).

Fifth, the Cancun Agreements establish a structure to assess the needs and policies for the transfer to developing countries of technologies for clean energy and adaptation to climate change, and a – as yet undefined – Climate Technology Center and Network to construct a global network to match technology suppliers with technology needs.

In addition, the Agreements attempt to provide an ongoing role for the Clean Development Mechanism (and some other market-oriented institutions launched under the Kyoto Protocol), and offer some special recognition of the situations of the Central and Eastern European countries (previously known in UN parlance as “parties undergoing transition to a market economy”) and Turkey, all of which are Annex I countries under the Kyoto Protocol, but decidedly poorer than the other members of that group of industrialized nations.

That’s the 32-page Cancun Agreements in a nutshell. As a member of one of the leading national delegations said to me in Cancun a few hours after the talks had concluded, “It’s incremental progress, but progress nonetheless.”

Are Such Incremental Steps Really a Success?

Recall from my November 19th essay that the best goal for the Cancun climate talks was to make real progress on a sound foundation for meaningful, long-term global action. I said that because of some fundamental scientific and economic realities, which I will not repeat here. In that previous essay, I also described “What Would Constitute Real Progress in Cancun” A quick comparison of my criteria from November 19th and the Cancun Agreements of December 11th tells me that the outcome of Cancun should be judged a success.

My first criterion of success was that the UNFCCC should embrace the parallel processes that are carrying out multilateral discussions on climate change policy: the Major Economies Forum or MEF (a multilateral venue for discussions – but not negotiations – among the most important emitting countries); the G20 (periodic meetings of the finance ministers – and sometimes heads of government – of the twenty largest economies in the world); and various other multilateral and bilateral organizations and discussions. Although the previous leadership of the UNFCCC seemed to view the MEF, the G20, and most other non-UNFCCC forums as competition – indeed, as a threat, the UNFCCC’s new leadership under Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres displays a positive and pragmatic attitude toward these parallel processes.

My second criterion was that the three major negotiating tracks be consolidated. These tracks were: first, the UNFCCC’s KP track (negotiating national targets for a possible second commitment period – post-2012 – for the Kyoto Protocol); second, the LCA track (the UNFCCC’s negotiation track for Long-term Cooperative Action, that is, a future international agreement of undefined nature); and third, the Copenhagen Accord, negotiated and noted at COP-15 in Copenhagen, Denmark, in December, 2009.

Permit me, please, to quote from my November 19th essay:

Consolidating these three tracks into two tracks (or better yet, one track) would be another significant step forward. One way this could happen would be for the LCA negotiations to take as their point of departure the existing Copenhagen Accord, which itself marked an important step forward by blurring for the first time (although not eliminating) the unproductive and utterly obsolete distinction in the Kyoto Protocol between Annex I and non-Annex I countries. (Note that more than 50 non-Annex I countries now have greater per capita income than the poorest of the Annex I countries.)

This is precisely what has happened. The Cancun Agreements – the product of the LCA-track negotiations – build directly, explicitly, and comprehensively on the Copenhagen Accord. The two tracks have become one.

Alas, the KP track remains, and a decision on a potential second commitment period (post-2012) for the Kyoto Protocol has been punted to COP-17 in Durban, South Africa, in December, 2011. It is difficult to picture a meaningful – or any – second commitment period for the Kyoto Protocol, with the United States out of that picture, and with Japan and Russia having stated unequivocally that they will not take up another set of targets, and with Australia and Canada also unlikely to participate. But note that this issue will have to be confronted in Durban a year from now. With the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol ending in 2012, COP-17 will provide the last opportunity for punting that contentious issue.

If you agree with my view – which I have written about in many previous blog posts – that the Kyoto Protocol is fundamentally flawed and that the Protocol’s dichotomous distinction between Annex I and non-Annex I countries is the heavy anchor that slows meaningful progress on international climate policy, then you will not consider it bad news that a second commitment period for the Protocol is looking less and less likely. On the other hand, you will, in that case, share my disappointment that the issue has been punted (recognizing, however, that had it not been punted, the Cancun meetings could have collapsed amidst acrimony and recriminations).

I also wrote in my November 19th post:

The UNFCCC principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” could be made meaningful through the dual principles that: all countries recognize their historic emissions (read, the industrialized world); and all countries are responsible for their future emissions (think of those rapidly-growing emerging economies).

The Cancun Agreements do this by recognizing directly and explicitly these dual principles. This can represent the next step in a movement beyond what has become the “QWERTY keyboard” (that is, unproductive path dependence) of international climate policy: the distinction in the Kyoto Protocol between the small set of Annex I countries with quantitative targets, and the majority of countries in the world with no responsibilities.

A variety of policy architectures can build on these dual principles and make them operational, bridging the political divide which exists between the industrialized and the developing world. (At the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, we have developed a variety of architectural proposals that could make these dual principles operational. See, for example: “Global Climate Policy Architecture and Political Feasibility: Specific Formulas and Emission Targets to Attain 460 PPM CO2 Concentrations” by Valentina Bosetti and Jeffrey Frankel; and “Three Key Elements of Post-2012 International Climate Policy Architecture” by Sheila M. Olmstead and Robert N. Stavins.)

My third criterion for success was movement forward with specific, narrow agreements, such as on: REDD+ (Reduced Deforestation and Forest Degradation, plus enhancement of forest carbon stocks); finance; and technology. Such movement forward has, in fact, occurred in all three domains in the Cancun Agreements, as I described above.

My fourth criterion for success was keyed to whether the parties to the Cancun meetings could maintain sensible expectations and thereby develop effective plans. This they have done. The key question was not what Cancun accomplishes in the short-term, but whether it helps put the world in a better position five, ten, and twenty years from now in regard to an effective long-term path of action to address the threat of global climate change.

Despite the fact that some advocacy groups – and for that matter, some nations – are no doubt disappointed with the outcome of Cancun, I think it is fair to say that this final criterion for success was satisfied: the Cancun Agreements can help put the world on a path toward an effective long-term plan of meaningful action.

Why Did Cancun Succeed?

If you agree with my assessment of success in Cancun, then a reasonable question to ask is why did the Cancun talks produce this successful outcome, particularly in contrast with what many people consider a less successful outcome of the Copenhagen talks last year. To address this question, let me expand on some points made in an insightful essay by Elliot Diringer, Vice President for International Strategies at the Pew Center on Global Climate Change.

First, the Mexican government through careful and methodical planning over the past year prepared itself well, and displayed tremendous skill in presiding over the talks. Reflect, if you will, on the brilliant way in which Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Patricia Espinosa, who served as President of COP-16, took note of the objections of Bolivia (and, at times, several other leftist and left-leaning Latin American countries, known collectively as the ALBA states), and then simply ruled that the support of 193 other countries meant that “consensus” had been achieved and the Cancun Agreements had been adopted by the Conference. At a critical moment, Ms. Espinosa noted that “consensus does not mean unanimity,” and that was that!

Compare this with the unfortunate chairing of COP-15 in Copenhagen by Danish Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who allowed the objections by a similar same small set of five relatively unimportant countries (Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua, Sudan, and Venezuela) to derail those talks, which hence “noted,” but did not adopt the Copenhagen Accord in December, 2009.

The Mexicans were also adept at facilitating small groups of countries to meet to advance productive negotiations, but made sure that any countries could join those meetings if they wanted. Hence, negotiations moved forward, but without the sense of exclusivity that alienated so many small (and some large) countries in Copenhagen.

The key role played by the Mexican leadership is consistent with the notion of Mexico as one of a small number of “bridging states,” which can play particularly important roles in this process because of their credibility in the two worlds that engage in divisive debates in the United Nations: the developed world and the developing world. We have examined this in our recent Harvard Project on Climate Agreements Issue Brief, Institutions for International Climate Governance. Mexico, along with Korea, are members of the OECD, but are also non-Annex I countries under the Kyoto Protocol. This gives Mexico — and gave Minister Espinosa — a degree of credibility across the diverse constituencies in the UNFCCC that was simply not enjoyed by Danish Prime Minister Rasmussen at COP-15 last year.

Second, China and the United States set the tone for many other countries by dealing with each other with civility, if not always with understanding. This contrasts with the tone that dominated in and after Copenhagen, when finger-pointing at Copenhagen between these two giants of the international stage led to a blame-game in the months after the Copenhagen talks.

As Elliot Diringer wrote, they may have recognized that “the best way to avoid blame was to avoid failure.” Beyond this, although the credit must go to both countries, the change from last year in the conduct of the Chinese delegation was striking. It appeared, as Coral Davenport wrote in The National Journal, that the Chinese were on a “charm offensive.” Working in Cancun on behalf of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, I can personally vouch for the tremendous increase from previous years in the openness of members of the official Chinese delegation, as well as the many Chinese members of civil society who attended the Cancun meetings.

Third, a worry hovered over the Cancun meetings that an outcome perceived to be failure would lead to the demise of the UN process itself. Since many nations (in particular, developing countries, which made up the vast majority of the 194 countries present in Cancun) very much want the United Nations and the UNFCCC to remain the core of international negotiations on climate change, that implicit threat provided a strong incentive for many countries to make sure that the Cancun talks did not “fail.”

Fourth, under the pragmatic leadership of UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres, realism may have finally eclipsed idealism in these international negotiations. Many observers have noted that many delegations – and probably most civil society NGO participants – at the previous COPs have misled themselves into thinking that ambitious cuts in greenhouse gases (GHGs) were forthcoming that could guarantee achievement of the 450 ppm/2 degrees C cap.

The acceptance of the Cancun Agreements suggests that the international diplomatic community may now recognize that incremental steps in the right direction are better than acrimonious debates over unachievable targets. This harkens back to what I characterized prior to COP-16 as the key challenge facing the negotiators: to continue the process of constructing a sound foundation for meaningful, long-term global action. In my view, this was accomplished in Cancun.

Further Reading

Some previous essays I have written and posted at this blog may be of interest to those who are interested in the Cancun Agreements. Here are links, in reverse chronological order:

Defining Success for Climate Negotiations in Cancun

Opportunities and Ironies: Climate Policy in Tokyo, Seoul, Brussels, and Washington

Another Copenhagen Outcome: Serious Questions About the Best Institutional Path Forward

What Hath Copenhagen Wrought? A Preliminary Assessment of the Copenhagen Accord

Chaos and Uncertainty in Copenhagen?

Only Private Sector Can Meet Finance Demands of Developing Countries

Defining Success for Climate Negotiations in Copenhagen

Approaching Copenhagen with a Portfolio of Domestic Commitments

Can Countries Cut Carbon Emissions Without Hurting Economic Growth?

Guest Post: Viewpoint on availability and quality

I received this from an industry contact who preferred to remain anonymous, but agreed to let me share this on Making Cents. They make some excellent points regarding the availability turnaround that has occurred in the industry (from oversupply to shortages) and regarding plant quality.

Over the last two plus years I have purchased from 65 nurseries and toured about 130 nurseries. I talk with plant brokers, propagators, and other nurserymen about plant availability, quality, and pricing in the market. I also attend several trade shows during the year. Geographically I am in contact with California, Oregon, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma, Tennessee, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland.

In general, plant availability is greatly reduced going into 2011 from 2010 levels. I have already seen this shortage on some items start this fall of 2010. Locating material to book for 2011 is more challenging. Plant quality may be in even greater decline. With the decline in plant numbers and quality, pricing is starting to go up. The rise in pricing will contribute to the shortage of plants available in the short term.

Plant availability across the industry has reduced for several reasons. Nurseries, from large to small facilities, are going out of business altogether. The ones that remain have planted smaller crops or no crop at all during 2010. I have not toured a nursery that has a larger or equal quantity of inventory at this point compared to last year. At best an individual nursery is down 30% in inventory numbers. Some are down 80%. This range holds true across those growers that are still operating. Many plants have remained on the growing location too long and have passed salable quality. Dumping significant numbers of old material has been common in 2010. In some cases the nursery did not have the labor remaining to dump the plants and have simply turned off the water. Those plants are dead in the growing space. In several nurseries small areas of ground cloth have been removed and vegetable gardens now occupy that irrigated space. Nurseries that specialize in propagating and selling liners are reporting lower than expected orders for material to be delivered in the 2011 planting season. This will contribute to a possible continuation of the shortage well into 2012.

Plant quality is of a bigger concern. Plants have been held too long in hopes of making a sale at some point in the future. Those plants are no longer viable for the retail trade and in many cases simply need to be dumped. Some growers have planted, yet not fertilized for various reasons ranging from lack of labor to put the fertilizer out to not having the money available to buy the fertilizer. Those plants will not be ready for sale in spring of 2011. Older and unfertilized plant material will result in fewer plants that can be purchased for 2011 retail sales. In one case the plants have been fertilized with chicken manure. This may result in additional weed pressure and an unpleasant odor. Speaking of weeds, they are abundant in many nurseries. Some plants cannot be purchased due to the overwhelming weed pressure at the grower. Again, lack of labor and money to hand weed and or put out herbicide.

Some growers whom are sensing the shortage are already quoting higher pricing. This phenomenon is beginning to spread. In recent weeks I have visited several nurseries that now have no hired labor and only the principles remain.

“I am not going to plant anything until I see the market turn.”

“We are not going to spend the money to fertilize until someone orders the plants.”

“I need several days notice to load a truck so that I can find some help, we do not have any labor left.”

“I am sorry for the weeds, we just do not have the labor or money to take care of them”

“We are too late planting anything this year and as a result will be basically out of salable plants during 2011”

“I went out to tour some of my plant sources and the first three I tried to tour were all closed and out of business.”

These quotes and more are quite common this day and age. I have no doubt that in 2011 there will be plant shortages. Some plants may not be found at all and some we may have temporary outages. Prices are going to go up.

How to Hone Your BS-Detecting Skills

This one was too good not to pass along.

Succeeding in business is all about accurately analyzing information and then making smart decisions. Falling for BS is antithetical to both. But with the world awash in half-truths, partial distortions, aggrandizing exaggerations and out-and-out lies you’ll have plenty of opportunities to fall prey to other people’s bull. How can you protect yourself from being led astray by their nonsense?

Washington, DC based venture capitalist Don Rainey penned a post for Business Insider’s War Room offering six suggestions to help you hone you BS detecting abilities. The piece is well worth a read in its entirety, but here are the basic suggestions with a few tidbits of my own thrown in:

- Determine what serves the other person’s self-interest. Whenever someone is presenting a point of view, you owe it to yourself to consider how their opinion might correlate to their own self-interest. After all, there must be some reason they have to make the argument to you in the first place. And that reason more likely correlates with their own self-interest than with yours.

- Question the data. We live in a world of pseudo science, skewed sample sets and anonymous experts. Don’t accept anything as an important truth without first examining the source. Know enough to know the difference. After all, 87.3% of all statistics are made up!

- Watch for truth qualifying statements. “To tell you the truth” or “Let’s be frank” or “I have to be honest…” are all statements that beg the question – “Are we starting to be honest just now?”

- Listen for name dropping. Credibility should always be derived from the strength of the argument, known facts and/or the reputation of the person present. If absent prominent people are the backbone of an argument, you should be suspect.

- Notice confusion in response to logical counterpoints. This type of response is meant to undermine your confidence in the soundness of your counter argument without seeking to specifically or factually oppose the point itself. Watch out for confusion when there should be none.

- Beware of the obvious. If a conversation provides you with one obvious thought after another, wait for the end of the train of thoughts as it is typically an illogical conclusion. After getting into a “yes…yes… yes…” rhythm, you may easily accept a well placed random conclusion or mistruth.